Roger Federer: A teenage hothead who found inner calm and became a unique talent

Federer has called time on one of the great sporting careers

The unsettling feeling first came watching Roger Federer’s meek defeat by Tommy Robredo at the US Open in 2013.

Then the realisation – the Swiss looked a little ordinary.

Federer, who is calling time on his career at the age of 41, was never supposed to look ordinary.

Ordinary was for mere mortals, players who sweated and toiled, for whom a racket was the tool of their trade not an extension of themselves.

At his best, Federer’s feet never seemed to touch the court, manoeuvring him effortlessly into position to swat away an impossible winner with the merest flick of his wrist.

The Swiss hangs up his racket as not just one of the best but one of the most loved athletes of all time, a sporting god inspiring devotion in millions worldwide.

Although Federer has defied the passing of time more successfully than most, that will not lessen the feeling of sadness that finally the end has arrived.

There will be sadness in the locker room, too, where he was known as friendly and approachable despite his stature, while his peers are all too aware how much they owe Federer for the benefits generated by tennis’ increased popularity.

The way things have played out would no doubt be a shock to the boy from the Swiss border city of Basel, who was a prodigious talent but also a hot-head prone to teenage tantrums and racket smashes.

It was not until he saw a psychologist and learned, Bjorn Borg-style, how to find his inner calm that he began to live up to his potential.

Federer’s first big moment in the limelight came at Wimbledon in 2001 when, as a 19-year-old, he beat grass-court king Pete Sampras in the fourth round.

He had already made his first ATP Tour final, in Marseille the previous year, losing to fellow Swiss Marc Rosset.

Federer was distraught, overcome by the feeling his chance of silverware might have gone. Rosset told him he need have no such worries.

It was a measure of Federer’s talent that, when he won his first grand slam title at Wimbledon in 2003, aged 21, there was a sense of ‘at last’.

And once he had the taste for it, he did not stop.

Between the start of 2004 and the end of 2007, Federer won 11 grand slam titles, losing an average of only six matches a year.

Yet there was no real agonising over whether one man’s dominance was killing the sport.

Every time Federer won, his interpretation of tennis as art seemed to sprinkle a little more stardust on the game.

He was twice denied a calendar Grand Slam, something achieved in the men’s game by only Rod Laver – twice – and Don Budge, after losing to Rafael Nadal in the final of the French Open.

And it is his rivalry with Nadal, of course, that will in many ways define Federer’s career.

Nadal has faced Novak Djokovic more times, but the Serbian has never been allowed to forget that he inserted himself into the era of the suave Swiss and swashbuckling Spaniard.

As well as the sensational matches Federer and Nadal played against each other, none better than the five-set marathon won by Nadal in the gloaming at Wimbledon in 2008, it was the complete contrast between the pair that captured the public’s imagination.

Federer’s game was about beauty and grace, his supreme athleticism barely noticed, while Nadal’s power was of an in-your-face brutality and the Spaniard was happy to grind out victories through the sheer force of his incredible mental strength.

Federer possessed great mental fortitude, too – his achievements are not possible without it – but the sense was always that for him it was not just about winning or losing but about how you played the game.

Although he enjoys a good relationship with Nadal that has strengthened throughout the years, the Swiss was never able quite to hide his belief that his game, built on attack and risk, was superior to his rival’s more pragmatic approach.

It frustrated Federer that defensive capabilities began to get on top, and perhaps one of his greatest achievements is that he managed to stay so successful while keeping his commitment to attacking tennis.

But Federer would never again dominate the sport the way he did for those four years.

One of his finest moments came in the summer of 2009 when, taking advantage of Nadal’s shock first loss at Roland Garros, he finally lifted the French Open trophy in his fourth final before going on to reclaim the Wimbledon crown.

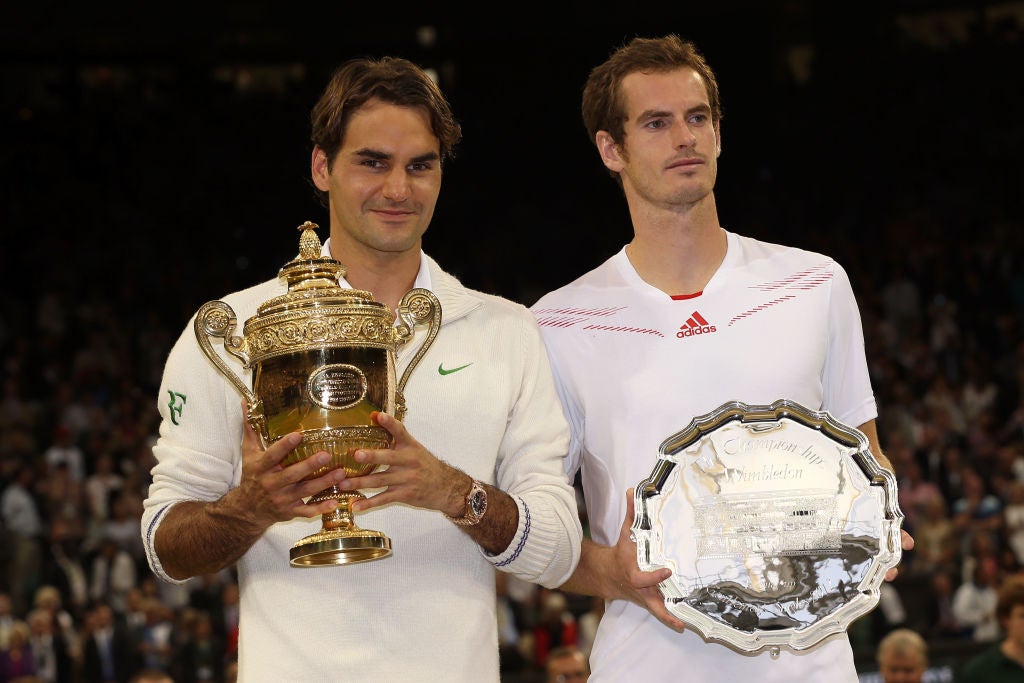

Three years later, with many questioning whether his grand slam-winning days were over, Federer beat Andy Murray to claim a seventh Wimbledon title.

There are those who see the Swiss as arrogant, and the role of gracious loser did not come easily when he began to taste defeat more often.

But gradually Federer adjusted to his new reality, no doubt helped by becoming a father to twin girls, and then, remarkably, twin boys – even his reproductive powers were superhuman.

When back problems contributed to a slump in form in 2013, and the end of his astonishing run of 36 straight grand slam quarter-finals, Federer allowed himself to reveal his doubts.

Heading towards his mid-30s, the odds were stacked against him, but Federer refused to allow age to stand in his way.

He recruited childhood hero Stefan Edberg as a coach and volleyed his way back to the Wimbledon final in 2014.

Nadal was increasingly affected by injury but now Federer found his path to more slam titles blocked by Djokovic, who beat him to the Wimbledon crown in successive years before winning another final battle at the US Open.

Then, just when it seemed Federer’s body had started to give out on him, he wrote the most remarkable chapter of all.

After six months out following knee surgery, 35-year-old Federer battled through to the 2017 Australian Open final where, fittingly, it was his old rival Nadal across the net.

Federer had not beaten Nadal at a grand slam in nearly a decade and it appeared the Spaniard had once again worn down his rival when he took a 3-1 lead in the fifth set.

But this time the story would not have the same ending. Federer attacked relentlessly and got a glorious reward – his 18th, and most unexpected, grand slam title.

He was not finished, winning a record eighth Wimbledon title the same year and then retaining his Melbourne crown in 2018.

Nadal and Djokovic closed in relentlessly, though, and Federer’s otherworldly records suddenly looked eminently catchable.

He reached one more slam final, agonisingly losing to Djokovic at Wimbledon in 2019 after holding two match points, before knee problems finally spelled the end.

The debate about who is the greatest of all time will rumble on, but tennis knows all too well there will never be another Roger Federer.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks