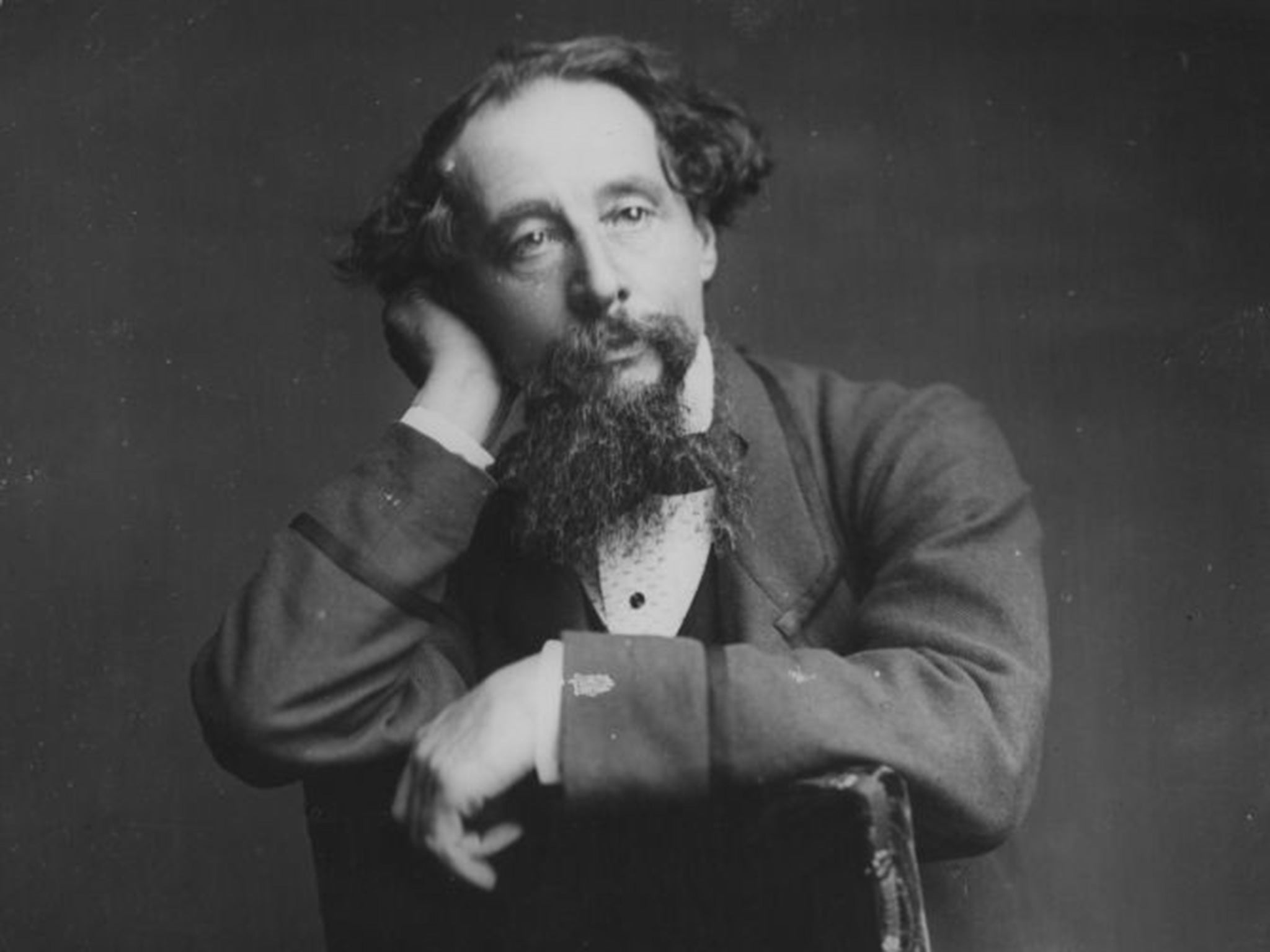

Charles Dickens: A most unusual celebrity endorsement for GOSH

Appalled by child mortality in the 1850s, Dickens was an early supporter of Great Ormond Street Hospital

At the time of the opening of the Hospital for Sick Children (as it was then named) at Great Ormond Street in February 1852, Charles Dickens was at the height of his powers, and writing one of his greatest novels, Bleak House. He was already known for his ardent support for child welfare causes, inspired by his own experiences of childhood poverty after his father was imprisoned for debt. Usefully for the new hospital, Dickens was living nearby at Tavistock House (on the site of today’s British Medical Association headquarters in Woburn Place) and appears to have already known Great Ormond Street’s founder, Dr Charles West, through fundraising for West’s former workplace, the Royal Universal Dispensary for Children at Waterloo.

As the first specialist children’s hospital in Britain, the Hospital for Sick Children was regarded with suspicion in some quarters, which Dickens addressed in the article “Drooping Buds”, published in his journal Household Words in April 1852. The piece forcefully promoted the urgent need for the hospital in a city with, by today’s standards, an appalling child mortality rate. Dickens also reported on the numerous other children’s hospitals already established and doing good work in other European countries, and his article provides the first detailed published description of the hospital in action after its opening.

With no National Health Service until 1948, the original hospital was entirely dependent on private fundraising and subscriptions, and by the end of 1857 was in severe financial difficulty. Dickens played a major part in its survival by chairing the first of what became a series of “Anniversary Festival” dinners in February 1858, at the Freemasons’ Tavern in Long Acre. His typically passionate and articulate speech helped to raise nearly £3000 (some £150,000 at today’s monetary values), enabling the hospital to survive and to enlarge by purchasing its neighbouring house at 48 Great Ormond Street. Later in 1858, Dickens raised more income for the hospital by giving public readings from A Christmas Carol at St Martin-in-the-Fields’ church hall.

During the year, Dickens separated from his wife, subsequently spending less time in London and more at his Kent home at Gad’s Hill, but he continued to take an interest in the hospital. In 1862, he commissioned his friend Henry Morley, a noted journalist and professor of English at nearby University College, to write an article, “From the Cradle to the Grave”, for Dickens’s journal All the Year Round, reviewing and complimenting the work of the Hospital for Sick Children to mark its 10th anniversary.

Dickens also featured a disguised advertisement for the hospital in his last completed novel, Our Mutual Friend, published in 1864-65. The orphan boy Johnny Higden is brought to “the Children’s Hospital” terminally ill with tuberculosis, and cared for properly for the first and only time in his life at “a place where there are none but children; a place set up on purpose for sick children; where the good doctors and nurses pass their lives with children, talk to none but children, touch none but children, comfort and cure none but children”.

The Dickens connection continued after the novelist’s death in 1870. His 1858 speech was reprinted as a fundraising leaflet for many years afterwards, and his great-granddaughter Monica Dickens, also a distinguished novelist and journalist, was a regular supporter of Great Ormond Street from the 1930s to the 1990s. In May 1994, a memorial plaque to Charles Dickens was unveiled in the hospital chapel in the presence of several of his great-grandchildren.

Of this great city of London – which, until a few weeks ago, contained no hospital wherein to treat and study the diseases of children – more than a third of the whole population perishes in infancy and childhood. Twenty-four in a hundred die during the two first years of life; and, during the next eight years, eleven die out of the remaining seventy-six.

Our children perish out of our homes: not because there is in them an inherent dangerous sickness (except in the few cases where they are born of parents who communicate to children heritable maladies), but because there is, in respect of their tender lives, a want of sanitary discipline and a want of medical knowledge. What should we say of a rose tree in which one bud out of every three dropped to the soil dead? We should not say that this was natural to roses; neither is it natural to men and women that they should see the glaze of death upon so many of the bright eyes that come to laugh and love among them – or that they should kiss so many little lips grown cold and still. The vice is external. We fail to prevent disease; and, in the case of children, to a much more lamentable extent than is well known, we fail to cure it …

Although science has advanced, although vaccination has been discovered and brought into general use, although medical knowledge is tenfold greater than it was fifty years ago, we still do not gain more than a diminution of two per cent in the terrible mortality among our children.

It does not at all follow that the intelligent physician who has learnt how to treat successfully the illnesses of adults, has only to modify his plans a little, to diminish the proportions of his doses, for the application of his knowledge to our little sons and daughters. Some of their diseases are peculiar to themselves; other diseases, common to us all, take a form in children varying as much from their familiar form with us as a child varies from a man. Different as the ways are, or ought to be, by which we reach a fault in a child’s mind, and reach a fault in the mind of an adult; so, not less different, if we would act successfully, should be our action upon ailments of the flesh …

The Hospital for Sick Children, lately established and now open, is situated in Great Ormond Street … quite fresh and white; bearing the inscription on its surface, “Hospital for Sick Children” … Crossing a spacious hall, we were ushered … up the spacious stairs into a large and lofty room, airy and gay …

The light laughter of children welcomed our entrance. There was nothing sad here. Light iron cribs, with the beds made in them, were ranged, instead of chairs, against the walls. There were half a dozen children – all the patients then contained in the new hospital; but, here and there, a bed was occupied by a sick doll. A large gay ball was rolling on the floor, and toys abounded …

There were five girls and a boy. Five were in bed near the windows; two of these, whose beds were the most distant from each other, confined by painful maladies, were resting on their arms, and busily exporting and importing fun … The most delightful music in this world, the light laughter of children floated freely through the place …

A sick child is a contradiction of ideas, like a cold summer. But to quench the summer in a child’s heart is, thank God! not easy. If we do not make a frost with wintry discipline, if we will use soft looks and gentle words; though such a hospital be full of sick and ailing bodies, the light, loving spirits of the children will fill its wards with pleasant sounds, contrasting happily with the complainings that abound among our sick adults… A child’s heart is soon touched by gentle people; and a child’s hospital in London, through which there should pass yearly 800 children of the poor, would help to diffuse a kind of health that is not usually got out of apothecaries’ bottles …

When we looked into the dead house, built for the reception of those children whom skill and care shall fail to save, and heard of the alarm, which its erection had excited in the breasts of some “particular” old ladies in the neighbourhood, we felt inclined to preach some comfort to them. Be of good heart, particular old ladies! In every street, square, crescent, alley, lane, in this great city, you will find dead children ...

They lie thick all around you. This little tenement will not hurt you; there will be the fewer dead houses for it; and the place to which it is attached may bring a saving health upon Queen Square, a blessing on Great Ormond Street.

An extract from ‘Drooping Buds’, by Charles Dickens

At the time of the opening of the Hospital for Sick Children (as it was then named) at Great Ormond Street in February 1852, Charles Dickens was at the height of his powers, and writing one of his greatest novels, Bleak House. He was already known for his ardent support for child welfare causes, inspired by his own experiences of childhood poverty after his father was imprisoned for debt. Usefully for the new hospital, Dickens was living nearby at Tavistock House (on the site of today’s British Medical Association headquarters in Woburn Place) and appears to have already known Great Ormond Street’s founder, Dr Charles West, through fundraising for West’s former workplace, the Royal Universal Dispensary for Children at Waterloo.

As the first specialist children’s hospital in Britain, the Hospital for Sick Children was regarded with suspicion in some quarters, which Dickens addressed in the article “Drooping Buds”, published in his journal Household Words in April 1852. The piece forcefully promoted the urgent need for the hospital in a city with, by today’s standards, an appalling child mortality rate. Dickens also reported on the numerous other children’s hospitals already established and doing good work in other European countries, and his article provides the first detailed published description of the hospital in action after its opening.

With no National Health Service until 1948, the original hospital was entirely dependent on private fundraising and subscriptions, and by the end of 1857 was in severe financial difficulty. Dickens played a major part in its survival by chairing the first of what became a series of “Anniversary Festival” dinners in February 1858, at the Freemasons’ Tavern in Long Acre. His typically passionate and articulate speech helped to raise nearly £3000 (some £150,000 at today’s monetary values), enabling the hospital to survive and to enlarge by purchasing its neighbouring house at 48 Great Ormond Street. Later in 1858, Dickens raised more income for the hospital by giving public readings from A Christmas Carol at St Martin-in-the-Fields’ church hall.

During the year, Dickens separated from his wife, subsequently spending less time in London and more at his Kent home at Gad’s Hill, but he continued to take an interest in the hospital. In 1862, he commissioned his friend Henry Morley, a noted journalist and professor of English at nearby University College, to write an article, “From the Cradle to the Grave”, for Dickens’s journal All the Year Round, reviewing and complimenting the work of the Hospital for Sick Children to mark its 10th anniversary.

Dickens also featured a disguised advertisement for the hospital in his last completed novel, Our Mutual Friend, published in 1864-65. The orphan boy Johnny Higden is brought to “the Children’s Hospital” terminally ill with tuberculosis, and cared for properly for the first and only time in his life at “a place where there are none but children; a place set up on purpose for sick children; where the good doctors and nurses pass their lives with children, talk to none but children, touch none but children, comfort and cure none but children”.

The Dickens connection continued after the novelist’s death in 1870. His 1858 speech was reprinted as a fundraising leaflet for many years afterwards, and his great-granddaughter Monica Dickens, also a distinguished novelist and journalist, was a regular supporter of Great Ormond Street from the 1930s to the 1990s. In May 1994, a memorial plaque to Charles Dickens was unveiled in the hospital chapel in the presence of several of his great-grandchildren.

Of this great city of London – which, until a few weeks ago, contained no hospital wherein to treat and study the diseases of children – more than a third of the whole population perishes in infancy and childhood. Twenty-four in a hundred die during the two first years of life; and, during the next eight years, eleven die out of the remaining seventy-six.

Our children perish out of our homes: not because there is in them an inherent dangerous sickness (except in the few cases where they are born of parents who communicate to children heritable maladies), but because there is, in respect of their tender lives, a want of sanitary discipline and a want of medical knowledge. What should we say of a rose tree in which one bud out of every three dropped to the soil dead? We should not say that this was natural to roses; neither is it natural to men and women that they should see the glaze of death upon so many of the bright eyes that come to laugh and love among them – or that they should kiss so many little lips grown cold and still. The vice is external. We fail to prevent disease; and, in the case of children, to a much more lamentable extent than is well known, we fail to cure it …

Although science has advanced, although vaccination has been discovered and brought into general use, although medical knowledge is tenfold greater than it was fifty years ago, we still do not gain more than a diminution of two per cent in the terrible mortality among our children.

It does not at all follow that the intelligent physician who has learnt how to treat successfully the illnesses of adults, has only to modify his plans a little, to diminish the proportions of his doses, for the application of his knowledge to our little sons and daughters. Some of their diseases are peculiar to themselves; other diseases, common to us all, take a form in children varying as much from their familiar form with us as a child varies from a man. Different as the ways are, or ought to be, by which we reach a fault in a child’s mind, and reach a fault in the mind of an adult; so, not less different, if we would act successfully, should be our action upon ailments of the flesh …

The Hospital for Sick Children, lately established and now open, is situated in Great Ormond Street … quite fresh and white; bearing the inscription on its surface, “Hospital for Sick Children” … Crossing a spacious hall, we were ushered … up the spacious stairs into a large and lofty room, airy and gay …

The light laughter of children welcomed our entrance. There was nothing sad here. Light iron cribs, with the beds made in them, were ranged, instead of chairs, against the walls. There were half a dozen children – all the patients then contained in the new hospital; but, here and there, a bed was occupied by a sick doll. A large gay ball was rolling on the floor, and toys abounded …

There were five girls and a boy. Five were in bed near the windows; two of these, whose beds were the most distant from each other, confined by painful maladies, were resting on their arms, and busily exporting and importing fun … The most delightful music in this world, the light laughter of children floated freely through the place …

A sick child is a contradiction of ideas, like a cold summer. But to quench the summer in a child’s heart is, thank God! not easy. If we do not make a frost with wintry discipline, if we will use soft looks and gentle words; though such a hospital be full of sick and ailing bodies, the light, loving spirits of the children will fill its wards with pleasant sounds, contrasting happily with the complainings that abound among our sick adults… A child’s heart is soon touched by gentle people; and a child’s hospital in London, through which there should pass yearly 800 children of the poor, would help to diffuse a kind of health that is not usually got out of apothecaries’ bottles …

When we looked into the dead house, built for the reception of those children whom skill and care shall fail to save, and heard of the alarm, which its erection had excited in the breasts of some “particular” old ladies in the neighbourhood, we felt inclined to preach some comfort to them. Be of good heart, particular old ladies! In every street, square, crescent, alley, lane, in this great city, you will find dead children ...

They lie thick all around you. This little tenement will not hurt you; there will be the fewer dead houses for it; and the place to which it is attached may bring a saving health upon Queen Square, a blessing on Great Ormond Street.

To Give to GOSH go to: http://ind.pn/1Mydxqt

To find out more about our appeal and why we're supporting GOSH go to: http://ind.pn/1MycZkr

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies